It’s interesting because I’ve been in Glasgow for 30 years, but I’ve never actually visited this part of the National Trust for Scotland. At the same time, it seems that virtually every accommodation I’ve used in Glasgow has been a tenement—tenements in the West End, tenements in the East End, and tenements in the South Side. The only time I haven’t stayed in a tenement was in the city centre, specifically in the Pollokshields area of Glasgow, which is a very nice inner suburb.

During the annual Doors Open Day in Glasgow, which took place a couple of weeks ago, I decided to visit the Tenement House located in the Garnethill section. It truly feels like a time capsule from 100 to 120 years ago.

The house was bequeathed to the city and later to the National Trust in the mid-1960s, after the owner neared the end of her life. I believe her daughter took over and rented some of it out. The National Trust acquired it in 1965.

It’s fascinating to have a conversation with someone and then, 100 years later, start that conversation again. Time stands still here.

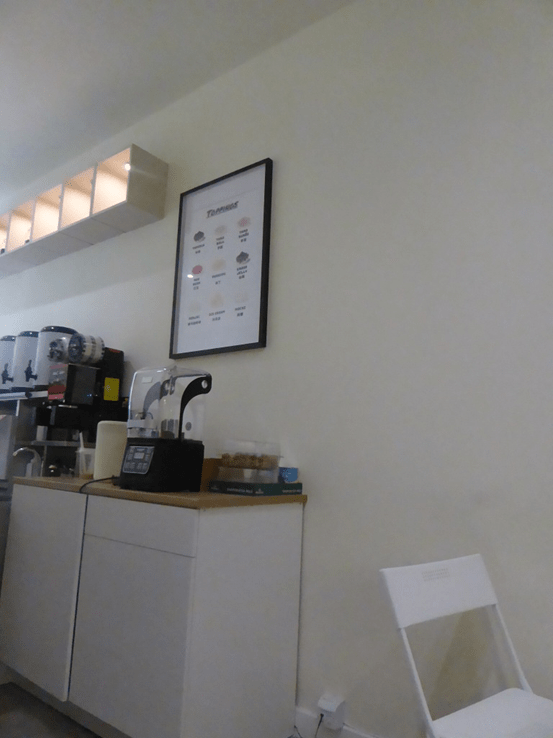

The overall layout is identical to so many tenements here in Glasgow, from the bed recesses (now used as a kitchen table area or closet):

To the “pully,” which is rather horrifically referred to as a Victorian hanger by some:

Additionally, it seems the lady who owned it was fairly well-off. While I was in the bathroom, three older Glaswegian women were describing what each feature in the room represented. They noticed a gas connection in the wall, which was connected to the gas port at the time, providing some of the heating and hot water. This suggests that the woman who owned the place was probably middle class.

Even in the bathroom, with a little paint and minor repairs, it would fit right in today.

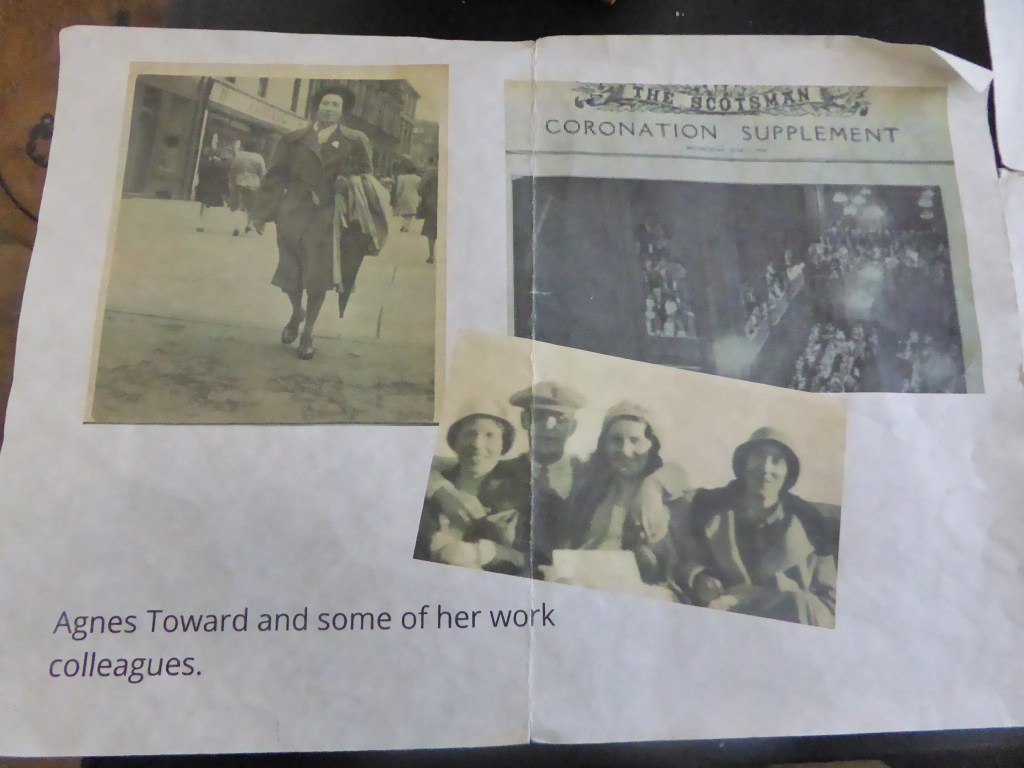

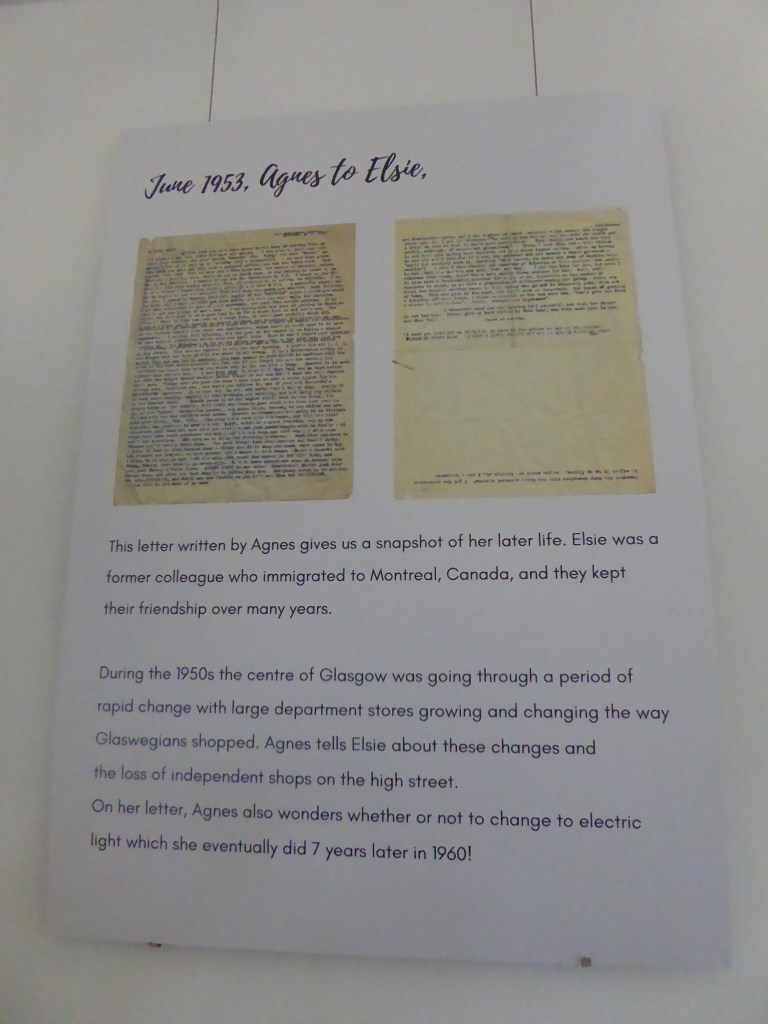

The most striking thing I saw was the letters and briefs that she had written and received throughout her life. It always strikes me that although we have everything from the internet to telephones and mass communication today, we’ve completely and utterly lost any form of communication via pen and paper. These letters were so much more eloquent and elegant than we use today; the words were utterly superior than what we could ever dream of crafting nowadays, even if we were to give up texting or emails.

CB